City’s Cash 1

A reading from the Holy Gospel according to John

And the Word was made flesh, and dwelt among us, and we beheld his glory, the glory as of the only begotten of the Father, full of grace and truth.

Please be seated.

In this passage at the beginning of John’s Gospel the Greek word for ‘dwelt among us’ – skenoo – is more literally translated as ‘tabernacled’ or ‘tented among us’.

John is telling us that, with the birth of Jesus, God is pitching his tent among us, as he had previously done in the midst of the people of Israel in the wilderness. He’s on the move again, exposed just as we are to the elements, to the powers and principalities, to the unruly fathoms of the human heart. Christians usually lump this lot together as Sin.

It’s a very rich semantic field, this verse from John.

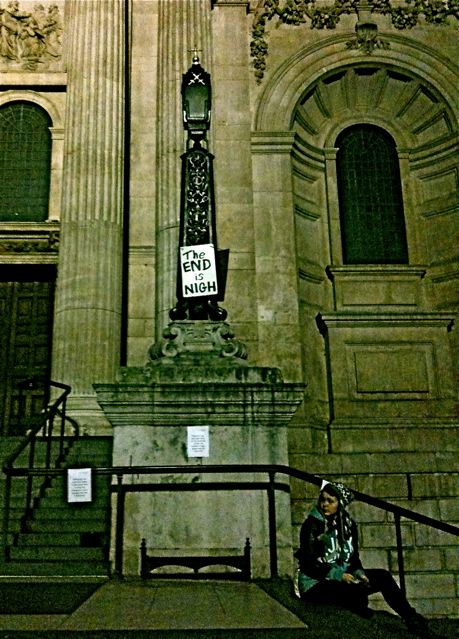

It’s almost as rich as the field of meaning in the encampment around the Cathedral Church of St Paul’s in the City of London. And because preaching a Word at Christmas, amidst the surfeit of festive cheer, is not an easy thing to do, I decide to take the 76 bus from Hackney into the City to go and visit the tent people for some inspiration.

It’s almost as rich as the field of meaning in the encampment around the Cathedral Church of St Paul’s in the City of London. And because preaching a Word at Christmas, amidst the surfeit of festive cheer, is not an easy thing to do, I decide to take the 76 bus from Hackney into the City to go and visit the tent people for some inspiration.

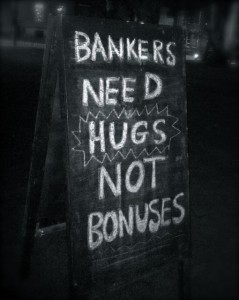

The bus passes the Finsbury Square encampment, which now looks like the morning-after-the-party. It’s become a field of mud with a deserted ‘info tent’ and a sign, fallen over in the breeze, offering ‘free hugs’ – but with no indication of any happy huggers to dispense them. The bus continues through the City, sloping along the wall of the Bank of England, and then loops round beside the Cathedral itself. I stay on and get out at the Royal Courts of Justice.

This is where the City of London Corporation is making its case in the High Court to rid itself of the campers. The City says that it does not object to lawful protest, but that it does not consider that the tents themselves are a necessary part of the protest. It says they are an obstruction on the public highway and they need to be removed.

I arrive just in time to hear the camp’s barrister cross examine the Registrar of the Cathedral (the chief administrator), Nicholas Cottam, who has been called as a witness in support of the City’s case for eviction.

I arrive just in time to hear the camp’s barrister cross examine the Registrar of the Cathedral (the chief administrator), Nicholas Cottam, who has been called as a witness in support of the City’s case for eviction.

Mr Cottam, a former Major General, says that he wishes to remain neutral in relation to the substantive issues raised by the camp, but that he has been particularly agitated from the start about the hazards of fire (amongst the other health and safety concerns). He says that, given the location of the tents and the emergency service’s reliance on Sat Nav devices, the fire brigade would be confounded by the camp were they ever required to extinguish a blaze in the burning building.

Maybe it is understandable that the administrator for Wren’s cathedral, which emerged from the cinders of the Fire of London, should be peculiarly sensitive to these incendiary dangers.

But the counsel for the campers is not entirely satisfied:

“A place of worship does not need to be wrapped up in metaphorical protective clothing does it?” he says in that leading way that barristers have, “the cathedral is surely a working building.”

“It is not a working building,” says Mr Cottam, “It is a sacred space – a place of sacred worship and respect.”

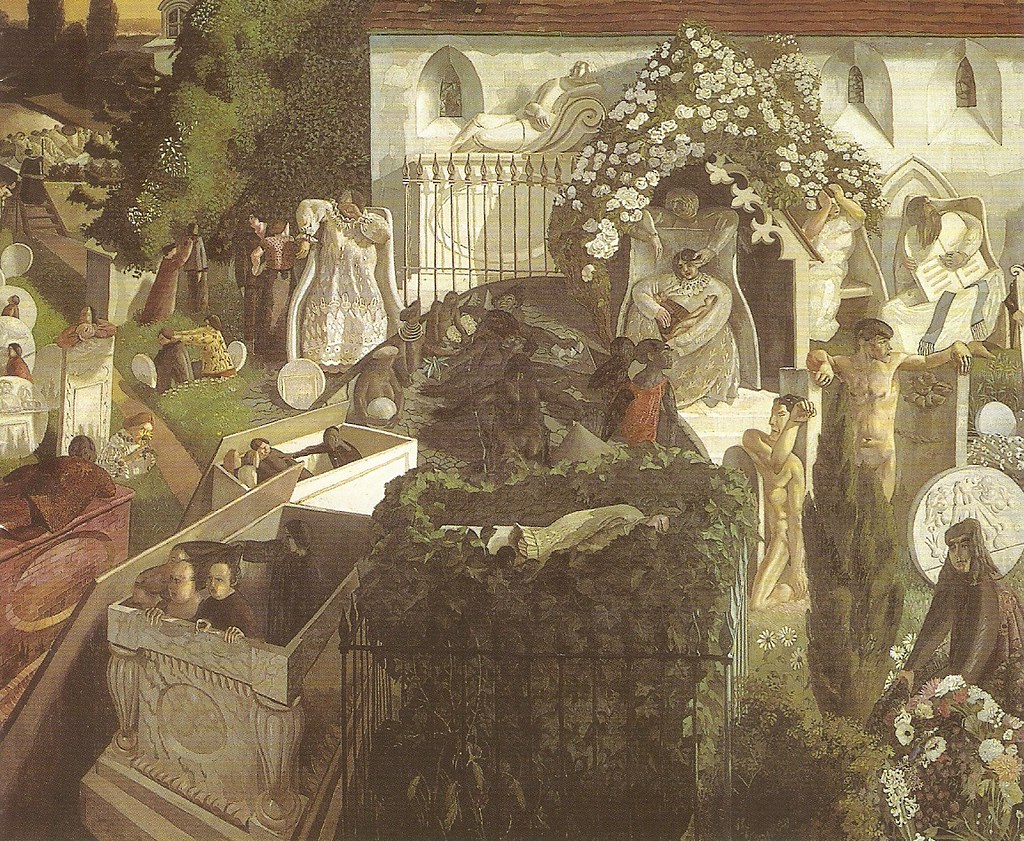

But what of ‘liturgy’, commonly understood as ‘the work of the people’, that is at the heart of that collective experience of sacred worship? Has London’s original dome become simply a grand mausoleum for state ceremonial performing cultic rituals of order and control? Have we forgotten that the building is itself no more than a big top with some fancy equestrian statues and a great acoustic?

When we identify too closely with these physical pillars we are in danger of taking our eyes from that pillar of fire that led the Israelites through the wilderness and will lead us also through the dark days ahead. To follow this fire we need to be ready to pitch and strike our inner Tent.

We have something to learn here from Jews who, annually at the feast of Sukkot, the feast of Tabernacles (or Tents), remind themselves of their years in the wilderness; that they are a people on the move.

If the camp is a judgment on the Church, recalling us to our biblical roots, it also a judgment on the City of London Corporation.

Occupy St Pauls’ daily General Assembly brings to mind the Saxon folk-moot that gathered at St Paul’s Cross in the churchyard of the Cathedral. This is where the City of London Corporation has its origins. This is where the Citizens of London historically deliberated on matters of common concern, in the lee of the Cathedral, and it is where they elected their Portreve, the office that became the Mayor after 1189, as well as their Chamberlain, the man responsible for the money.

Although the current High Court action to evict the tent people is lodged in the name of the “Lord Mayor, Commonalty and Citizens of London” – legally a body corporate, constitutionally representing a balance of interests amongst the Citizenry – in much of its operational life the City Corporation has come to represent the single interest of capital.

Although the current High Court action to evict the tent people is lodged in the name of the “Lord Mayor, Commonalty and Citizens of London” – legally a body corporate, constitutionally representing a balance of interests amongst the Citizenry – in much of its operational life the City Corporation has come to represent the single interest of capital.

And so we have a situation in which the oldest democratic institution in the world has now become a lobby group for the financial services, the ‘business city’.

“We have no ‘authority’ to take on this role [promoting the business city],” concedes Stuart Fraser (the current Chairman of the City’s Policy and Resources Committee) in an exchange of letters with me at the time when I was also a City Councillor, “which is why it is funded from our private funds – City Cash.”

No one knows for sure how much money is in this particular pot because the City Corporation refuses to publish the accounts. The City puts the total equity amount in the Cash at around £1 billion. Some say, however, the funds are at least double that. As the consolidated accounts below show there is about £500M tied up in cash. Because the City doesn’t put a value on its vast property portfolio these figures are all speculative and more work still needs to be done on unravelling these accounts.

But how can money held in trust for the Citizens of London be considered ‘private’ money? And on what grounds can it be used to promote the ‘business city’, a role the Chairman of Policy concedes the City Corporation has no ‘authority’ to perform, beyond that which it gives itself and that which Parliament, in turn, allows?

Statements of accounts are not just financial ledgers. They are also moral inventories. They reveal our priorities and expose our commitments. Our January credit card statements bear witness to this. The City of London Corporation should not be fearful of publishing the Cash Accounts.

The Gospel writer’s story of the Word ‘dwelling among us’ is also a judgement on our well-defended distinctions between what is private and what is public.

In this new age we are called to participate in a common life where we belong to one another in mutual dependence and with mutual accountability. At times this may be place of windy exposure and vulnerability. It’s a campsite.

If we let them do so the tents may remind both the Cathedral and the City of our origins.

But in the end they will be swept away.

In the end we will all be swept away. There is no abiding city.

For now let’s remember faithfully, with grace and truth, where we have come from and whose we are and be thankful.

And all for His sake.

Parish Notices

Summary information relating to the 2006/7 City’s Cash accounts may be downloaded here: City’s Cash, 2007

For more information on the background to the City’s Cash go to Reclaim the City

For further Midrash by BBC London News reporter Paraic O’Brien go here and by AOL finance journalist Adrian Holliday go here

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post