On the Eve of All Hallows

It is almost exactly 12 years since I became a vicar in Stamford Hill and about eight years since I received a letter from Hugh’s widow with a cheque in it.

She wanted me to buy a bench in memory of her late husband who had died some thirty years previously and whose ashes had been interred somewhere in the church garden. Particularly she wanted something for her children who had suffered greatly because of his sudden death at the age of 40.

I had never met any members of her family but a few of the congregation remembered her and the struggle she had gone through to raise her three sons. We banked the cheque and I wrote to her to say that we would certainly be happy, in due course, to provide a bench in memory of her late husband.

“In due course”- that’s a nicely evasive timespan. It wasn’t entirely clear to me where we would put another bench in our tiny Garden of Remembrance and besides there was a children’s nursery running riot in our hall and our priority was to prevent the grass turning into a mud chute.

Each year we prayed for Hugh around the anniversary of his death but for reasons not only to do with my disorganisation the bench itself never materialised. Hugh’s widow left occasional prompts on my answer machine, reminding me of my earlier commitments (and the cheque), to which I responded sheepishly that we were still working on it.

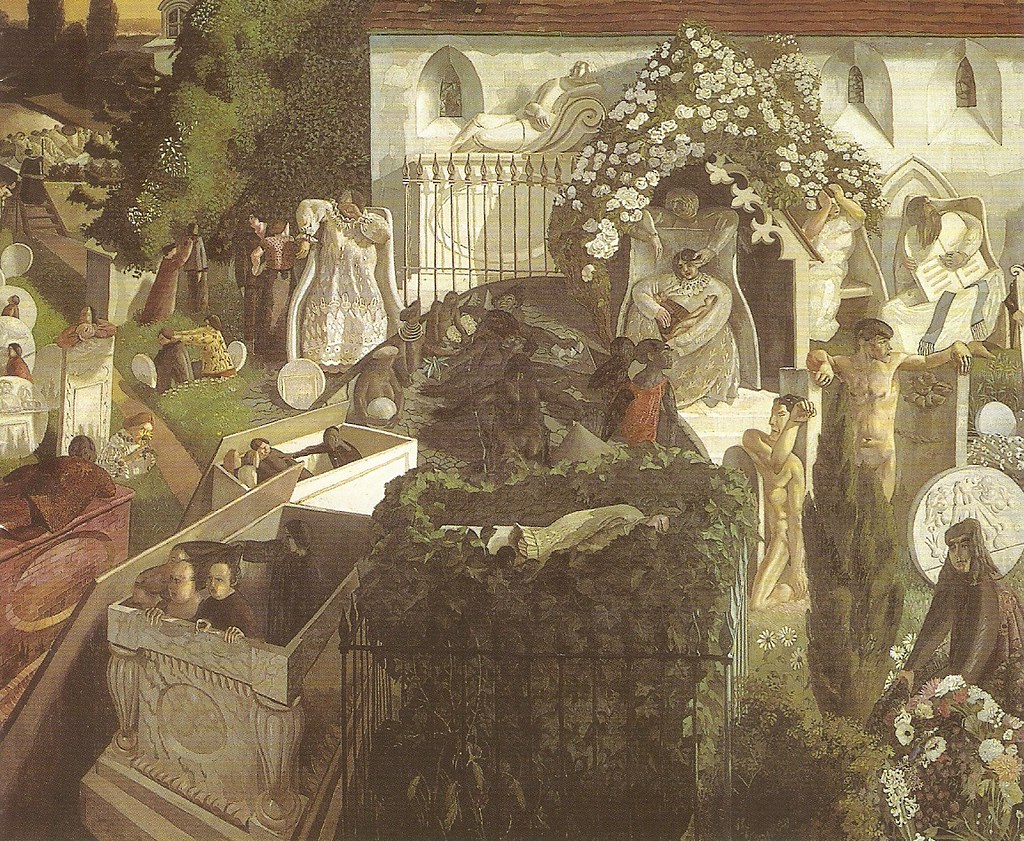

photo Kristin Perers

One day I met a woman on the neighbouring housing estate who asked me if I was the new vicar. Not that new, I said. Oh, that previous vicar, she said, a very lazy man. He promised to buy a bench for my friend in memory of her dead husband and she gave him a cheque and then he took the money and never got the bench. I’ll look into it, I said. That’s very kind of you, she said.

During lockdown we had a man sleeping rough in the garden. He kipped down on the bench which sat beneath the plum tree just inside the gate. I don’t know if it was him or just the passage of time but quite soon after he left the bench began to disintegrate. Still I hesitated.

Early on Sunday mornings I go and preach my sermon, by way of rehearsal, to the dead at Abney Park Cemetery. I look out for signs of a mighty stirring. It was that reading from the book of Revelation, the one with the man sat on the throne making his wild unfeasible promises: “See I am making all things new.” Promises, certainly, but also a judgement.

As I’m leaving the cemetery I notice, for the first time, that there’s a greenwood furniture maker operating by the entrance. I go back during the week and speak to one of the wood workers, a man called Spenser.

Over the next few weeks we exchange some design ideas and drawings and costings and the church council commissions a new bench for the space beneath the plum tree.

It turns out, when we look into the records, that this is the very spot where Hugh’s ashes were interred some 40 years previously.

In recent weeks we have had the builders repainting the vicarage as part of scheduled works. Kristin and I shuffle from room to room as workmen’s shadows appear across the windows. That’s what it can feel like at this time of year as we prepare for the feast of All Saints and then All Souls when we remember friends and family members who have died.

In recent weeks we have had the builders repainting the vicarage as part of scheduled works. Kristin and I shuffle from room to room as workmen’s shadows appear across the windows. That’s what it can feel like at this time of year as we prepare for the feast of All Saints and then All Souls when we remember friends and family members who have died.

Over the past eighteen months we have held the memory of those who have died during the pandemic with name pasting ceremonies at Liberty Hall and drumming circles on the Common as well as improvised graveside funerals, raw yet necessary. Parish churches are there for the whole community and this is one reason they need to be saved.

Our memorial bench also arrived this week. We put it in the corner below the plum tree. Although it is one piece of wood, English Oak, it is two pieces of furniture. We have placed these at a slight angle to one another so that conversation is easier between two people, not least in these days of social distancing.

Hugh was forty when he died and it is now forty years since he died. The bench allows you to sit and speak with the deceased across the gap. You can empty chair your loved one.

Where conversations often end abruptly at death, seemingly in mid sentence, in our garden of remembrance they can continue. Our two-in-one bench insists that our fractured lives will be repaired in that place where death will be no more, where mourning and crying and pain will be no more, where all things will be made new. In due course.

Hugh’s son visits the bench given in memory of his father whose ashes were interred at this spot 40 years ago

Hugh’s son visits the bench given in memory of his father whose ashes were interred at this spot 40 years ago