Ascension Day

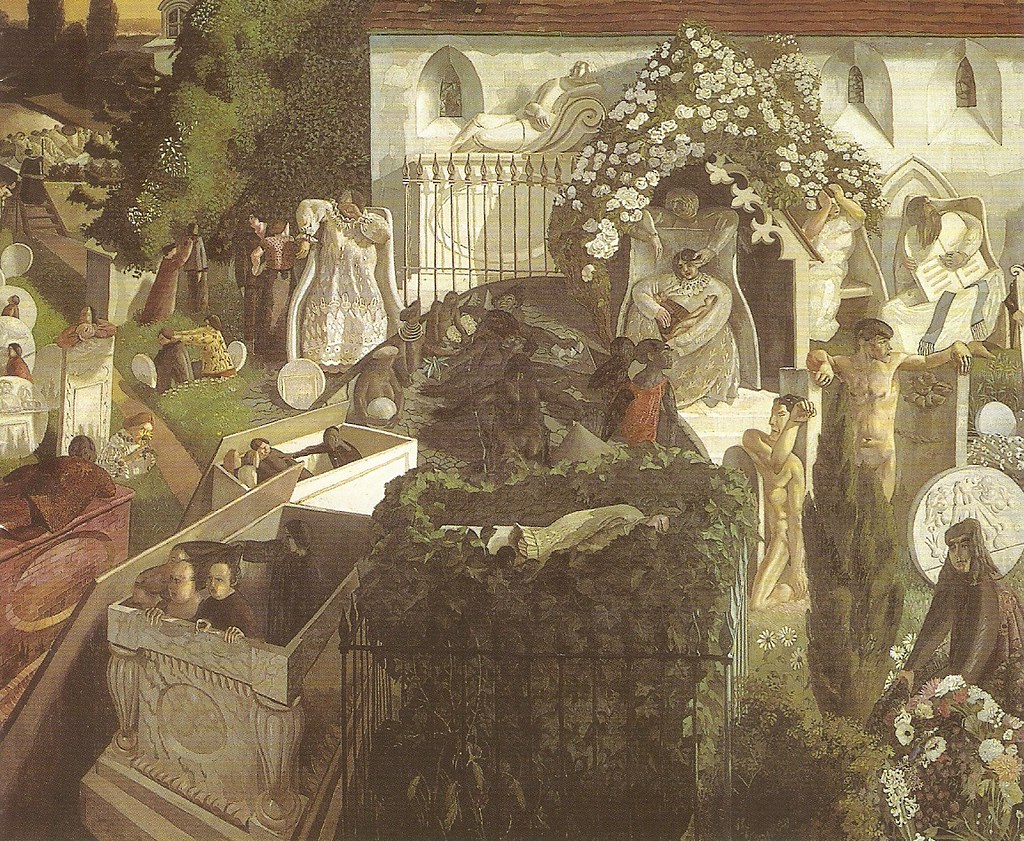

Today is Ascension Day. The last three days have been “rogation days”, days of prayer and fasting and preparation before today’s great festival of the Church when our Lord takes His place throughout all eternity at the right hand of the Father. So much so straightforward.

Today is Ascension Day. The last three days have been “rogation days”, days of prayer and fasting and preparation before today’s great festival of the Church when our Lord takes His place throughout all eternity at the right hand of the Father. So much so straightforward.

Rogation days are days of asking. That’s actually where the word “rogation” comes from, in Latin. As in ‘an interrogative statement’, a statement that also asks a question. This is the sort of thing they teach you in theological college and it keeps you going through an entire ministry.

Traditionally it’s during these days of rogation before Ascension Day that a parish priest goes out onto the farms and into the fields and asks for God’s blessing on the land and the crops. If Rogation Sunday in May is the call, then Harvest Festival in October is the response. Over these three days of rogation we ask the question to which Harvest is the answer, we make the petition in anticipation of her blessing.

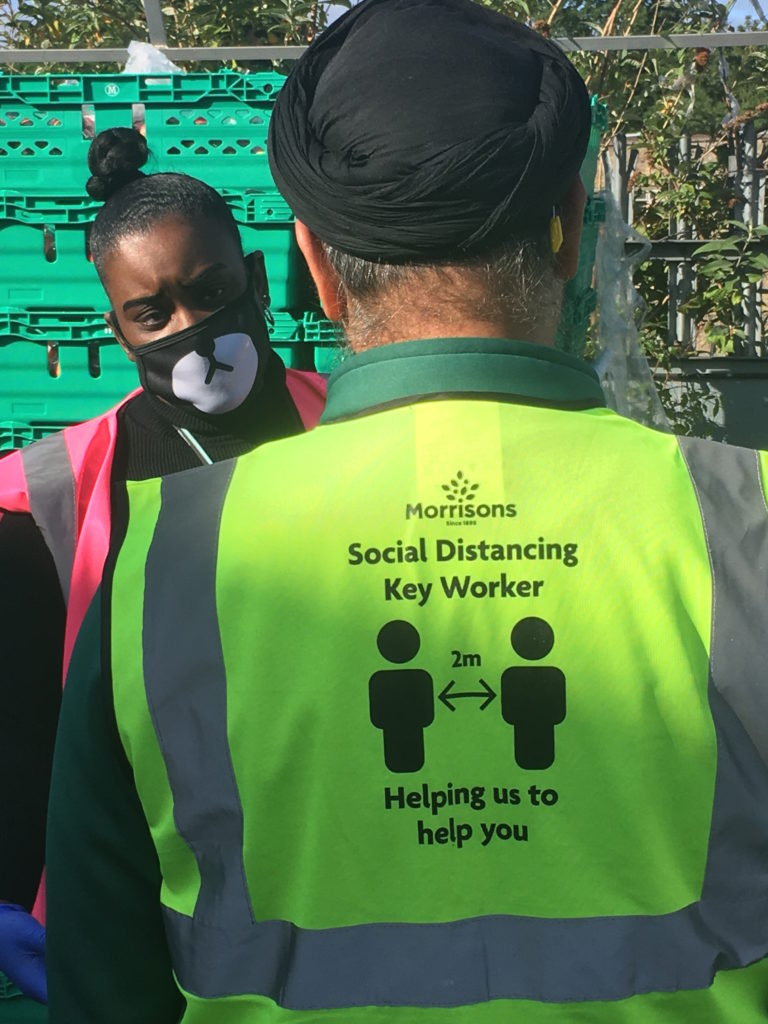

Things are a little different in downtown Hackney, but still I head out with my social distancing stick this week to beat the bounds of my parish. But instead of calling in at the farms I go to the supermarkets and shops and thank the workers for keeping the show on the road during the lockdown of the last couple of months.

I go to see Mr Master at the post office and Mr Patel at the newsagent. I visit the chemist, the baker and the take-away pizza guy. I go to the builders merchants on Stamford Hill and the petrol station on Clapton Common. I give the bin-men a thumbs up as they trundle by in their truck and I knock on the window of a rather startled looking postman, quietly minding his own business in his van.

Actually everyone is pleased, if a little surprised, to be thanked. Immediately they tell you how tough it’s been, not so much complaining as bearing testimony.

In Stamford Hill we have a bus depot and when I go to thank the drivers for keeping London moving one driver’s voice breaks when he tells me how worried he’s been that he will catch the virus and infect his family, including his elderly father. But everywhere there is also a strong sense of duty. That this is simply what we do.

My friend Maurice Glasman has come up with a definition of “the working class” – that these are the people who can’t work from home. While many of us have carried on pretty much as before, with our laptops and our Zoom meetings, others have left the safety of their home to keep our city open for the rest of us during the lockdown.

These are the people, visible now in a new way, that I thank as I walk through my parish. But there is also a challenge buried in my greeting.

Why has it taken a pandemic to recognise the status and sacrifice of the working class? How can we stop taking our fellow citizens for granted?

It’s actually a statement with a question. An interrogative statement, you could say.