No Questions Asked: The City goes to the Polls

The Square Mile is getting ready to elect 100 councillors on Thursday 24 March. This is the topsy turvy world of the City Corporation where the Bank of China is registered to vote but the Bank of England isn’t and where a sanctioned Russian finance house gets to send a dozen workers to the polls but one of my parishioners, who has worked in the City for years as a cleaner, has been denied a vote by the Town Clerk on the grounds (amongst others) that if she were granted one it might impact the outcome of the election in her ward.

Welcome to the Corporation of London.

You could say that its unique franchise reflects the anomalous nature of the City itself and is a pragmatic arrangement rooted in its history. Or you could say it is a voting system that subordinates the practice of democracy to the interests of international capital and has managed to escape closer public scrutiny only because of the cover provided by the Corporation’s role as a powerful lobbyist for the Financial Services. Maybe both are true.

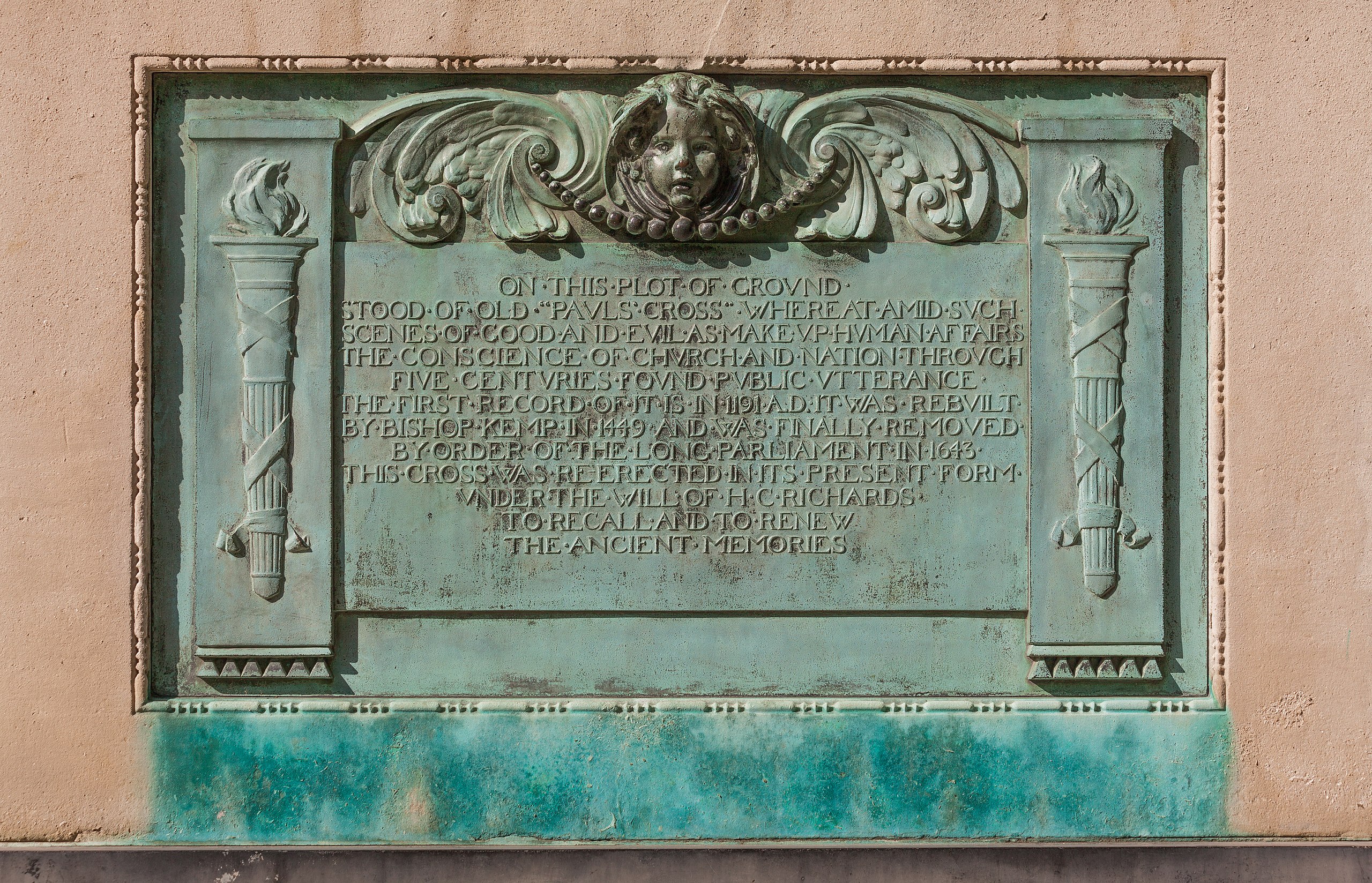

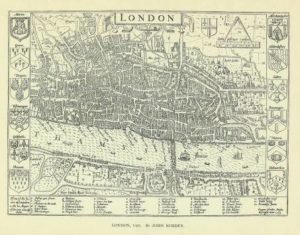

With its origins at the Saxon folkmoot at Paul’s Cross, the City Corporation is one of the oldest democratic assemblies in the world. At the base of the early 20th Century memorial that commemorates the corner of the cathedral’s churchyard where St Paul’s Cross once stood is a plaque which invites us still “to recall and to renew the ancient memories.” Voting is one way we do this.

It may not currently amount to a very robust mandate for the scale of the institution at the disposal of its elected officials but at least it’s a reminder of the covenant that exists between the City and its putative constituency.

The City of London is part of our Ancient Constitution alongside the Church and the Crown. And even if you’re left unmoved by the claims that it bears in its institutional body the common law rights and privileges of the Freeborn Englishman you may still acknowledge its importance to the exchequer’s balance of payment accounts.

That’s why what goes on here is all our business. And it’s why it matters that my parishioner’s application to become a “worker voter” was refused by the Town Clerk, first administratively and then on appeal. I’ll tell you a bit more about this in a moment but first let me explain how the City’s franchise actually works.

*

Like everywhere else in the UK residents get to vote. In the City, however, there aren’t too many of them and this year only 6200 registered across the Square Mile. That amounts to about half an average sized ward in the London Borough of Hackney or the number of fans attending a rainy midweek fixture at Leyton Orient. It’s not a meaningful electorate for a body politic with multi-billion assets and a medieval Guildhall in which the Lord Mayor routinely hosts heads of state at banquets and sundry receptions.

In the 1990s the City came up with a formula that adapted the existing business vote (abolished everywhere else in the UK in 1969). This new proposal allowed companies and other institutions to appoint voters depending on the size of their workforce. Political theorist Maurice Glasman says that the nearest analogous franchise may be found in the arrangements put in place in the Antebellum South where plantation owners were granted voting entitlements dependent on the number of slaves they owned. Certainly the worker vote in the City is considered to be a privilege and not a right. It is up to the bosses of the firm whether or not any voting appointments are to be made.

This means that individuals such as my parishioner, Comfort, may request a vote (as she did) but the qualifying body for which she works may simply ignore her (as it did). This year about 12,800 workers are registered to vote, which is less than half the total number of possible voting appointments if every qualifying body took up its entitlement. Between the residents and the workers the electorate is still only about 19000.

Aside from those who have simply not responded to the electoral officer’s importuning emails this year over 260 qualifying bodies expressly told the City that they had no intention of enfranchising their workers and could the electoral office please stop bothering them. One of these companies is the American bank Goldman Sachs. I was on a call with the director responsible for fielding such enquiries at the bank. He actually seemed pretty mystified by the whole thing and said that Goldman Sachs had taken the decision that they wanted to remain apolitical. Consequently they would not be permitting their workers to vote. It did not seem to occur to him that withholding the vote from the workers was itself a political act.

*

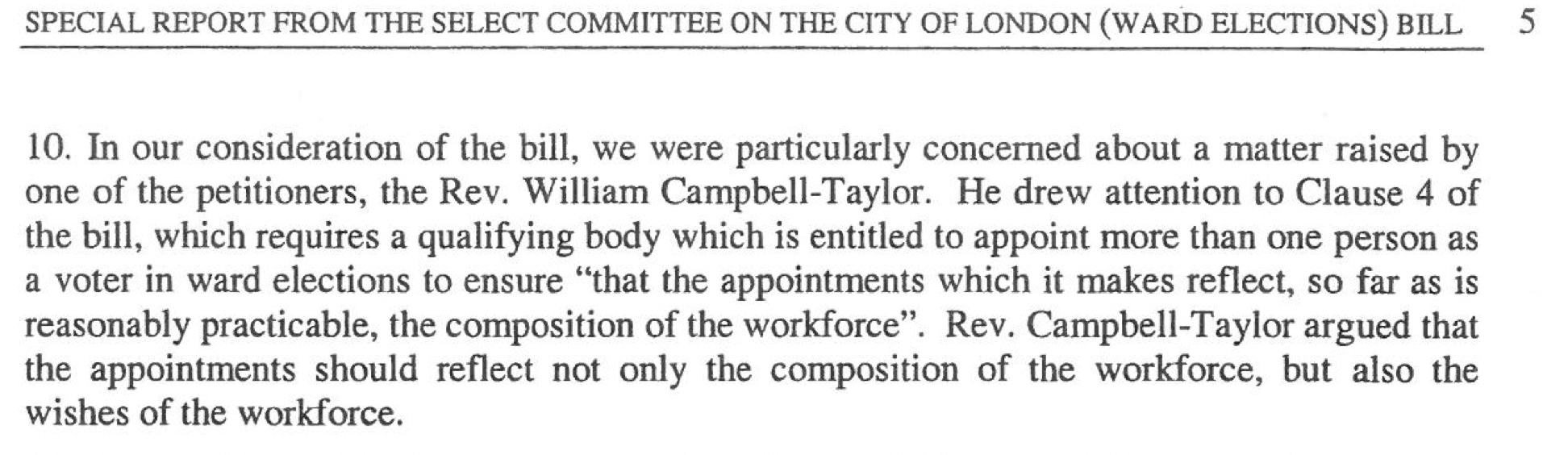

These voting arrangements were put in place by the City of London (ward elections) Act 2002, almost exactly twenty years ago. There is one other key provision in this Act – Clause 4 – which stipulates that the voting appointments which a company makes “should reflect, so far as is reasonably practicable, the composition of the workforce”. I petitioned this particular clause when the Bill passed through the Committee stage in the House of Lords, arguing that this requirement, as it stood, was essentially unenforceable and consequently meaningless.

In October 2002 the committee heard my case. This is how the chairman of the committee, Lord Jauncey, put it in the Report:

The committee went on to require a number of undertakings from the City of London before it sent the legislation back to the Commons for its third and final reading. It wanted to make sure that the process of making voting appointments should be “open and clear”. Indeed in his report Lord Jauncey stipulated (at paragraph 14) that the guidelines given to companies should explicitly include a reference to this.

From the Hansard record, this is how Lord Rennard led the discussion around this undertaking:

LORD RENNARD: Say there is a large company which is a qualifying body and say it has 29 electors who have the chance to vote for members of the council or aldermen, etc. What I think we are bothered about is to make sure we do not get to a point where Fred and Harry sit in a corner and Fred and Harry pick the 29 people who would be entitled to vote.

What I am suggesting, basically, is that we need to know who actually – somebody within the qualifying body or company – has the power to say that these 29, or these 15 or these 50 people will have a vote in these elections. Who, actually, is eventually taking the decision that these people have a vote and on what basis are they doing it? They are asked to take into account the idea that they should reflect the composition of the workforce, but how are they doing this and when are they doing it?

We want to avoid a situation arising where the employees in the workforce have perhaps seen all these guidelines, understand that their organisation is now to be represented and given some votes, but just find out afterwards that the people who have got votes were these people and who appointed them?

TOWN CLERK: Could I just take the words down?

LORD RENNARD: Something to the effect of “that the process of appointments in any event should be an open one, in which everyone understands who makes the appointments, when and on what basis”..

TOWN CLERK: As it stands at the moment, the names and the organisations they represent would actually be published in the form that people could object to. You would have a right of objection.

LORD RENNARD: Can you explain to me the list of potential electors?

TOWN CLERK: The list can be challenged in the Lord Mayor City of London’s Court from somebody who believes that they should have been included.

LORD RENNARD: Perhaps, if I suggest that is a last resort —-

TOWN CLERK: It is a last resort, yes. Could I just consult my colleagues? (After a short pause) We would be content with putting in “that the process of appointment should be open and clear”. The bit “which everyone understands who makes the appointment … etc, etc” we think would be very difficult to establish.

LORD MARSH: Not to say optimistic.

TOWN CLERK: Indeed. I would be comfortable with “that the process in any event of appointment should be open and clear”.

When I looked again at the registration forms given to companies I noticed that all this talk of openness and clarity had been quietly dropped. I asked the City’s lawyer about this. He said that the phrase was somewhere on the website but that it didn’t need to be on the physical registration form to meet the undertaking to Parliament. Oh really?

*

The City may not be known for its transparency but at least you can go in to Guildhall and inspect all the ward lists at any point in the year.

The officers are extremely helpful and they will sit you down at a desk and ask you to fill in a form and they will even provide you with copies to take away. You half expect to be offered a flat white with oat milk as you are handed the print outs.

When I went into the electoral office recently, a prospective candidate with his nose in a ward list was already there, checking to see who had signed up for the vote. There are 25 wards in total, many of them little changed since Saxon days, which means that many are small, often with only a few hundred voters. If you are going to stand for election you want to know that your friends and colleagues have bothered to register. They could make the difference between victory and defeat. He was huffing and puffing his irritation that a number who had promised to fill in the forms had failed to do so.

When I went into the electoral office recently, a prospective candidate with his nose in a ward list was already there, checking to see who had signed up for the vote. There are 25 wards in total, many of them little changed since Saxon days, which means that many are small, often with only a few hundred voters. If you are going to stand for election you want to know that your friends and colleagues have bothered to register. They could make the difference between victory and defeat. He was huffing and puffing his irritation that a number who had promised to fill in the forms had failed to do so.

But was not this a case of Fred and Harry sitting in the corner deciding who gets the vote? I asked the electoral officer whether a qualifying body’s submission was required to detail how its voting appointments actually reflect the composition of its workforce.

She said that the list of voting appointments is signed off by the qualifying body but without any explanatory statement. The City accepts it in good faith. It is never checked, or at least not routinely. As it turns out this requirement is not even stated on the registration form.

So the terms of Clause 4 to “ensure that the voting appointments reflect the composition of the workforce” were essentially unenforceable and consequently meaningless?

Hmm, she said.

We simply don’t hold the information to confirm one way or another, and so we don’t, she said.

You would have thought that the City could ask for a simple statement about how the voters reflect the composition of the workforce. It seems that they don’t even bother to ask the question?

At this point the candidate offered us the benefit of his lived experience and said that as far as he knew, at his insurance company in Gracechurch Street, no one had never taken any notice whatsoever of any such composition or diversity requirement.

But it’s the law, I said.

Not that I know of, he said, as though that was fine then.

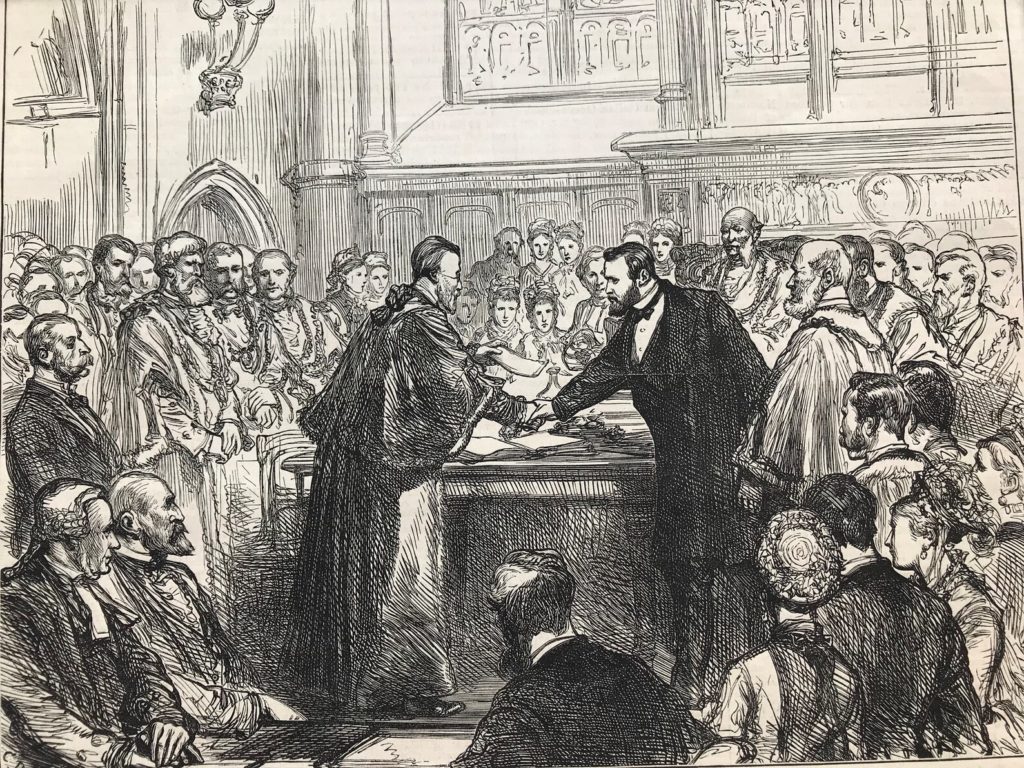

Tsar Ivan IV meets traders from the City of London in Moscow in 1554

I went back to my ward list. I wondered whether I was becoming a bit of franchise anorak. I continued to scan the voters registered along Cornhill. And there, nestling between a cluster of wealth managers and venture capitalists was what I was looking for: VTB Capital PLC. This Russian bank, recently sanctioned by the Government and delisted by the London Stock Exchange was here on the Walbrook ward list, all trussed up and ready to vote in this week’s ward election. I felt a little thrill of indignation.

The candidate and I left the electoral office together and we went down in the lift. It turns out that he was a serving councillor in a unitary authority in Buckinghamshire. He said he was keen to throw his hand into the ring in the City.

“In fact, I should have done it years ago” he said, a little wistfully, as though the possibility of serving as a councillor in the City of London was akin to taking early retirement, a lifestyle choice that he fully anticipated would greatly increase his personal satisfaction.

As I wandered off to find my bike I wondered what it was about this City Everyman that I didn’t like. Was it his sense of overwhelming entitlement, his firm belief that the system was simply there to find a way round? And find a way round surely he would.

*

By its very nature capital exists in a watery realm. It will evade banks and trenches and find its way easily through the flood plains into the open seas. It has a particular fondness for a number of Caribbean destinations such as the Cayman Islands or the British Virgin Islands. It’s true that financial liquidity may bring fertility and abundance to the nations, but first you need to dig irrigation channels to direct and manage the flow. This is where the practice of democracy comes in. It’s why voting matters. It’s why my parishioner’s story matters.

My parishioner Comfort is not a company director and nor does she have a punchy portfolio of equities. She’s not directly affected by the buoyancy or otherwise of the property market. But like many of us she’s worried about paying her heating bill, covering the weekly shop as well as saving something to spend on her grandchildren or visiting her family in Ghana. She may rely on public services but not on state benefits. For the last thirty years she’s worked through the night cleaning City offices for their daytime occupants and she is part of an army of low paid workers that keeps the economy going, many of whom live in my corner of the London Borough of Hackney and none of whom can “work from home”.

Where, on the ward lists, are the kitchen porters, the security guards and the warehousemen? The post room workers and the facility operatives? The receptionists and telephonists, the drivers, the shop workers and sales staff? Where are the cleaners? Where are the people who actually have to turn up somewhere to do their job? Or does finance capitalism in the City of London only serve the interests of the Zoom room?

I’ve noticed that the chair of the City’s policy committee has started talking about breaking the “class ceiling” which I think is about diversity at board level. But first the City should be concerned to get low paid workers, such as Comfort, onto the ward lists and into the polling booth. Inclusion needs to start on the shop floor.

*

The qualifying body that had refused Comfort a vote was, ironically, the Corporation of the City of London itself. Everywhere else in the Square Mile the Corporation was out and about championing the franchise with flyers and LinkedIn mailshots, targeted tweets, a fleet of cold calling interns and a six foot cardboard Griffin that was hoicked from station to station during the rush hour like it was part of Freshers’ Fair. But for its own workers, of which there are several thousand spread out across the Square Mile, including Comfort, it did not lift a finger.

Over the last twenty years the City has had a blanket practice of not registering its own workers but it has never formally adopted such a policy. Comfort’s application to become a voter and then her subsequent legal challenge provoked a last-minute flurry at the Guildhall. In December 2021 it tabled a late item and agreed a policy on the day that applications to join the ward list closed. One of the most telling moments in the debate took place when an entirely straight-faced committee member announced that she could not support giving the corporation workers the vote because it might impact the outcome of an election. No one raised an eyebrow. Indeed the committee chair said that for her this was also a “distinguisher”. It’s possible to view the meeting on YouTube and I write about this here.

A small team of pro bono lawyers helped me draft Comfort’s response. They referred to the late arrival of the policy after Comfort had submitted her application and to the fact the new policy was made without reference to Section 4 of the 2002 Ward Elections Act and without reference to the Public Sector Equality Duty (PSED) under Section 149 of the Equality Act 2010. In all of this they referred to the City’s failure to consider the merits of individual requests for registrations, hiding under a blanket practice and now policy which was partly predicated on the absurdity of refusing a cleaner (and other corporation workers) the vote lest it impact an election.

The Lord Mayor’s court was presented to Comfort as the route for a legal challenge but we asked for an informal hearing in front of the Town Clerk, as also permitted by some obscure bit of a Representation of the People Act, and were granted one. It was the cheaper option. In the end I went to represent Comfort myself, rehearsing the legal arguments in my head as I took the 149 bus along the Kingsland Road. I met with the Town Clerk and a couple of City solicitors in Guildhall. Frankly I felt a little exposed as I struggled to remember my lines, referring at one point to the PTSD rather than the PSED, and found myself saying something ridiculous like, “you will have to forgive me but as a clergyman I know more about grace than I do about the law.” The City Comptroller told me that his brother-in-law was a clergyman and that it was a fine profession and he offered to go and get me a glass of water.

Then he told me I was whistling in the dark. None of that stuff applies to us, he said. We’re an ancient body by prescription and not a local authority or a creature of statute. We have no statutory public sector equality duty in relation to the franchise. We don’t have to produce any impact assessments. There is no obligation on firms to appoint voters. Basically the City can do what it wants. Besides, in law, the grounds for a challenge to the ward list are extremely narrow and Comfort simply has not met them. She has not been nominated by a qualifying body and that’s the end of the matter. But thank you for your interest.

A few days later we received a letter formally setting out the City’s case and why we were barking up the wrong tree. At the end of the letter he offered some advice: “In all the circumstances, therefore, it seems to me that should your Client and the Reverend Campbell-Taylor seek to have the Corporation’s policy changed they should do so through political means.”

*

The relationship between law and politics is of course a dynamic one and free speech and public deliberation are its necessary corollaries. This was the case made in 1644 by that son of the City, John Milton, in his prose work Areopagitica. Addressed to the Long Parliament he spoke of the need for uncensored printing as he drove the argument for freedom down to its fundamental principles. For Milton freedom had its roots in a directly mediated covenant between God and His people, unsullied by the hierarchies of the established church. He saw London, with its dissenting citizens, as the place where that covenant would find its fullest expression as he spoke in apocalyptic terms of “a city of refuge, the mansion-house of liberty, encompassed and surrounded with His protection.”

Milton was born a stone’s throw from Guildhall in the ward of Bread Street, which tucks around the site of St Paul’s Cross like a protective elbow. Born in 1608 he would have been familiar with the history of the folkmoot. This was where the Freeborn had gathered before the Norman Conquest to elect their leaders, or so it was said. Maybe it was at the very moment that St Paul’s Cross was dismantled in the 1630s that these “ancient memories” stirred most fiercely in the youthful imagination of this early modern poet. Certainly this is the era that saw a flourishing of the idea of the “ancient constitution” – see the writings of the jurist Edward Coke – as a locus of resistance to the high-handed rule of Charles I. Providence seemed to lay her hand on Milton.

Milton was born a stone’s throw from Guildhall in the ward of Bread Street, which tucks around the site of St Paul’s Cross like a protective elbow. Born in 1608 he would have been familiar with the history of the folkmoot. This was where the Freeborn had gathered before the Norman Conquest to elect their leaders, or so it was said. Maybe it was at the very moment that St Paul’s Cross was dismantled in the 1630s that these “ancient memories” stirred most fiercely in the youthful imagination of this early modern poet. Certainly this is the era that saw a flourishing of the idea of the “ancient constitution” – see the writings of the jurist Edward Coke – as a locus of resistance to the high-handed rule of Charles I. Providence seemed to lay her hand on Milton.

Such a vision would not survive the convulsions of the Civil War and then the Glorious Revolution in 1689 as a couple of key shifts took place in the late 17th Century.

First, in philosophy: John Locke took John Milton’s mystical vision and recast it as a political theory. In doing so Milton’s love of liberty became Locke’s doctrine of the social contract, as set out in his second Treatise on Civil Government in 1690. Contract overtook covenant. Here Locke argues that we give up our equality and executive power for the sake of preserving liberty and property. He repeatedly says that “government has no other end than the preservation of property” and it was this insistence on the priority of property that enabled the emboldened merchant adventurers of late seventeenth century to lay claim to the territories in which they found themselves.

And not just the territories, the peoples too. It was at this time that the first slaves were taken in Africa and the triangular trade with the Caribbean and Great Britain took shape. At first it was regulated by the Royal African Company which had received a chartered monopoly from Charles II in 1672. Yet there emerged almost immediately an active campaign in the City of London which claimed that the right to trade in slaves was a deeply cherished English liberty and challenged the Crown’s monopoly in the very name of freedom. And so the lobbyists for freedom, relying on Locke’s defence of property interests, relying on Milton vision of the freeborn, pioneered Europe’s contribution to the largest forced migration in human history. This is the argument in William Pettigrew’s book on the Royal African Company, Freedom’s Debt.

The second key shift in the seventeenth century followed on from this and was political. The City was invited to extend its administration over the ever increasing number of those filling the suburbs outside the City walls. In 1633, at roughly the same time that St Paul’s Cross was dismantled to make way for Inigo Jones’ facelift of the medieval cathedral, the Privy Council asked Guildhall whether “in the interests of better government” it would consider extending its jurisdiction over the neighbouring districts around the City – Clerkenwell, Hoxton, Shoreditch, Spitalfields, Whitechapel, Hackney. Many of the new inhabitants in these places had made their way into the city from the country following enclosures. The City thought about it and then declined the invitation. The Privy Council asked again a year later. The City declined again. It became known as ‘The Great Refusal’.

At the same time that it was turning its back on the rapidly expanding suburbs of London, the City was finding new horizons of interest in a network of trade routes that stretched across its emerging maritime empire: China, Russia, Africa and of course the Americas. As its locus of interest contracted on land, it expanded across the oceans. Throughout the 17th Century its wealthy citizens speculated through a number of joint stock trading companies including the Virginia Company (1606), the East India Company (1599) and the earliest of them all, the Muscovy Company, founded in 1551 to find the North East passage to China. The first adventurers didn’t find the route to China but they did attract the attention of Tsar Ivan IV and were summoned to his court in Moscow where they exchanged wools for furs and established a trading partner and an important diplomatic link between Muscovy and England.

*

Four hundred years later this shift from land to sea is still apparent in the way the franchise works. It has bequeathed a situation whereby a cleaner who lives in one of those new London suburbs is still unable to register a vote but 11 workers at a sanctioned Russian bank in Walbrook ward will be able to stroll past the Bank of England and the Royal Exchange and cast theirs in the polling station in Mansion House itself, at the heart of the City of London, on 24 March.