Gresham Fund 2

A reading from the Gospel of Matthew:

So whenever you give alms, do not sound a trumpet before you, as the hypocrites do in the synagogues and in the streets, so that they may be praised by others. Truly I tell you, they have received their reward. But when you give alms, do not let your left hand know what your right hand is doing, so that your alms may be done in secret; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you.

Please be seated.

Earlier this year the Hackney Preacher was looking into what happened to Sir Thomas Gresham’s bequest. Through his Will, signed in 1575, he made over his fortune in trust jointly to the City Corporation and the Mercers Livery Company, for the purposes of contributing towards “the proffitte of the common weale.”

Earlier this year the Hackney Preacher was looking into what happened to Sir Thomas Gresham’s bequest. Through his Will, signed in 1575, he made over his fortune in trust jointly to the City Corporation and the Mercers Livery Company, for the purposes of contributing towards “the proffitte of the common weale.”

Specifically, he gave it for the benefit the poor, to assist prisoners and to set up a teaching College in the City of London, along the lines of those found in Oxford or Cambridge.

So what happened to this money and where is this college? Where are the prisoners who continue to receive the benefit? Which poor?

I asked Greg Williams, the City’s Head of Media.

He told me that whereas the Gresham Charity continued to serve these ends, the Gresham Estate had been absorbed into the City’s Cash, the City’s private money.

In fact, this is what said:

“The Gresham Estate is part of City’s Cash and the legal obligations upon the City of London Corporation under the terms of Sir Thomas Gresham’s will are delivered through the Sir Thomas Gresham Charity. The City of London Corporation funds the net expenditure of this charity. The income from the Estate is not held on trust but belongs to the City Corporation as beneficial owner.”

All clear? The left hand knowing exactly what the right hand is doing?

But, here’s a question:

Where does a bequest held in charitable trust end . . . and a beneficial ownership begin?

Answer:

In court.

You see, in 1885, there was a dispute between the City Corporation and the Inland Revenue over the rental income from the Royal Exchange, part of the Gresham bequest. The City said that it was not liable to pay tax on the surplus income because, ahem, it was only held in trust as part of the original moiety.

In other words The City, at this time, claimed that they were not the beneficial owner.

The Master of the Rolls, sitting in the Court of Appeal, disagreed, overturning an earlier judgement of the Divisional Court and concurring with the Inland Revenue that the rent belonged to the Corporation for their own benefit absolutely and that consequently tax was payable – see Chartres and Vermont, A Brief History of Gresham College, Gresham College, 1998, p 75.

Still, the City Corporation disagreed. We’re not the beneficial owner! We’re going to take the case to the House of Lords!

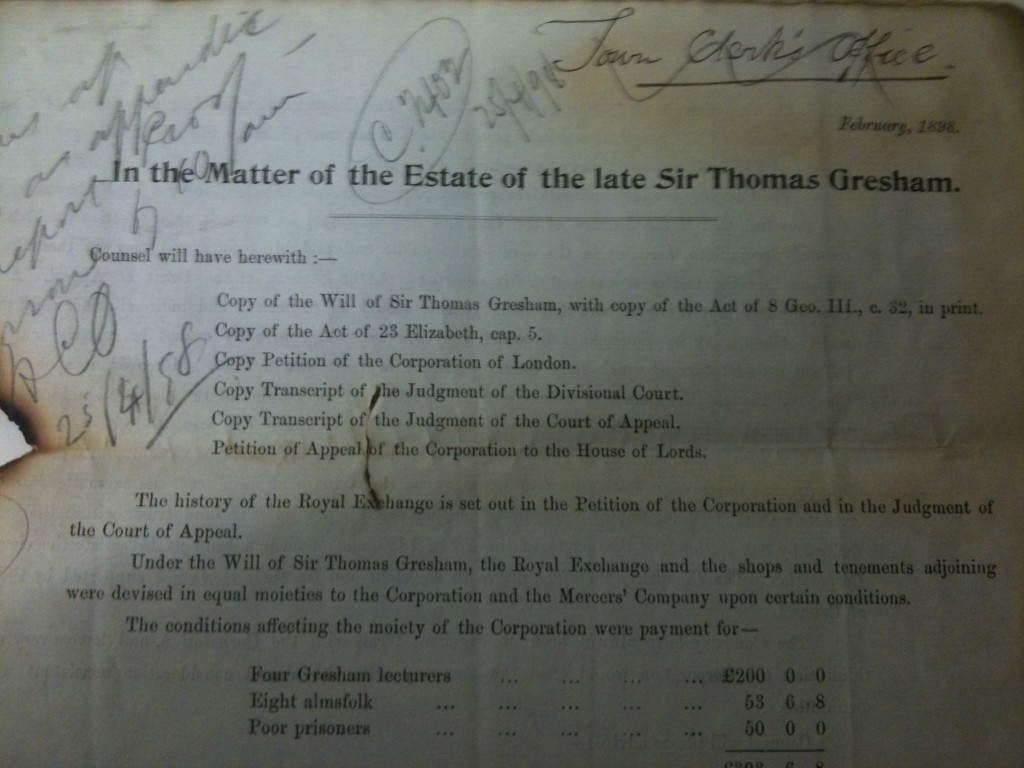

In fact, in the London Metropolitan archive, the Hackney Preacher found half incinerated legal papers from leading Counsel for the Mercers Livery Company dated Feb 1898.

The legal advice warns of the dangers of such an Appeal:

“Should the Appeal prove successful it is probable that some scheme would be insisted upon by the Crown which would in effect take the disposition of the surplus funds out of the hands of the Corporation and Company respectively, and possibly cause them to be applied to objects or in a way which neither the Corporation nor the Company might desire.”

This, of course, remains the City Corporation’s fear in relation to the City’s Cash and it may also be the reason that the Petition of Appeal was never pursued nor the case ever tested. The City thought it prudent to “concede” ownership and pay its tax liability. And so it has proved.

On what grounds, however, could such an Appeal be made, even now, by way of challenge?

This is the way it works. A Court tries to determine a testator’s intention. What was his actual Will? This is decisive in any challenge. This principle was established in the late sixteenth century – a period of rapid inflation – where the problem often arose. In G H Jones’ book, the History of the Law of Charity, 1532-1827 (Cambridge, 1969), there is a discussion about a related matter in which the author states, “It is not insignificant that in every reported case before the beginning of the eighteenth century, the charity was given the benefit of the increase in value.” (p. 92).

So we need to ask: Did Gresham intend to give the whole of his land’s rent at any time to charity? Or was his intention merely to devise a fixed sum of money or to meet a fixed purpose and give the rest to the City to do with what they want?

As the legal Counsel in 1898 says, “something may be urged from [Sir Thomas Gresham’s] words, whereas I do mean the same to the Common Weal“.

Here is how Richard Chartres, the current Bishop of London, puts it:

“No doubt, like other Tudor patriachs, Sir Thomas would have passed the bulk of his estate to his son and heir Richard, had not the boy died in 1564. Gresham’s natural daughter Anne, who married Francis Bacon’s elder half-brother Nathaniel, also died before her father, and so when Thomas Gresham came to make his Will in 1575 he was free, having made provision for his wife, to consider other ways of disposing of his vast fortune.” (p. 6, A Brief History of Gresham College).

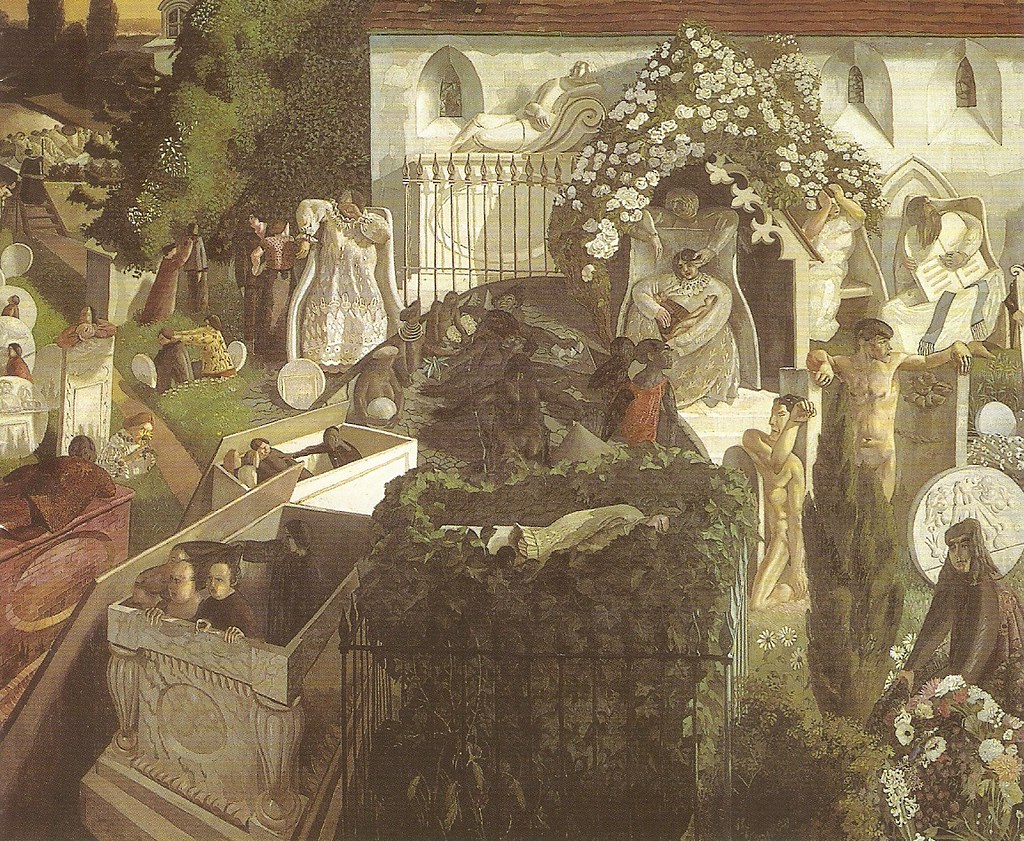

In 1575 Gresham was a man facing his own appearance in that final Court of Appeal and he was settling his accounts accordingly. One imagines that his interests were pretty philanthropic.

Greg Williams, the City’s Head of Media, suggests, however, that Gresham’s interest was essentially commercial, as a trader and merchant, and that he would frankly be pretty relaxed with the way the City Corporation has chosen to deploy his bequest through the City Cash.

“And how is that?”

“Various philanthropic purposes for the benefit of all Londoners,” he says without blinking.

Though obviously, as a private fund, he’s not at liberty to discuss this in detail. The distribution of the alms is done in secret. The left hand need not know what the right hand is doing. While both hands may remain deep inside the trouser pockets.

And all for His sake.

Previous Post

Previous Post Next Post

Next Post