The miracle of the tap

The church leaks from the cement ceiling and the crypt is pretty damp too. Water is rising from the ground and descending from the heavens and sometimes I wonder whether the ark of salvation will survive the coming storm.

The church leaks from the cement ceiling and the crypt is pretty damp too. Water is rising from the ground and descending from the heavens and sometimes I wonder whether the ark of salvation will survive the coming storm.

We patch things up as best we can but actually we need a whole new roof. The parapet also needs fixing. Our Georgian tower needs repairing and repainting. Our 1773 Whitechapel Foundry bell, which dates the original church, has stopped sounding because it needs a new hammer but to replace the hammer we will need to improve access to the belfry and that’s another £500 for aluminium ladders right there.

I could spend all day of every day fundraising for this or that. But then the new Dean of Mission rings up and asks me to walk him through our strategy for evangelism. What’s your plan to grow the church? he asks. He doesn’t just want us to secure the ark; he wants us to fill it too.

I get an email from the diocesan finance officer asking where our monthly cheque is (answer: in the post). The Diocese of London, like everyone else, is worried about balancing the books. The bishops want us to increase our market share or as they put it “make new disciples”. In the meantime with the limited resources we have as a parish, I spend my time as a facilities manager and events organiser rather than a provider of what the prayer book calls “ghostly counsel”.

A month ago we launched a Crowdfunder to raise money to put our undercroft at the disposal of a whole bunch of excellent community projects including a martial arts school, a counselling service, a mindfulness circle, a yoga-for-tots class, a Caribbean cookery enterprise making hot food for isolated elders. You get the idea.

But where is Jesus in all of this? asks the Dean of Mission, reminding me that the diocese is subsidising my post. It’s true: despite our monthly cheques, some of which arrive, my church is a net receiver of money from the Diocese of London. What will happen if they turn the tap off? As my bishop points out to me the current situation is unsustainable: “I don’t think it’s likely to be possible for [support across the area] to continue at the same level as it has been.”

*

I think about all of this as I sit in the church each day after the midday Angelus. Tearing myself away from my grant applications for an hour I set a few lanterns ablaze around the altar and fire up the chancel with an incense burner while I pump Bach cantatas through the sound system. A few people wander in and add the names of those who have died to our list. They light a votive candle and say a prayer and then leave with a wave.

I’ve been talking to an expert in church mission about what I can do to keep my church from closing. He tells me about the three Ps of evangelism: Presence, Proclamation and Persuasion. Presence is about hosting events and outreach programmes, it’s about generating relationships and trust. Proclamation is sharing the Gospel, inviting people into a relationship with Jesus. Persuasion is an ugly way of describing what I would call surrendering to the presence and action of God.

My corner of the church, Catholic Anglicanism, is generally good at the first and last of these. But crap at the second. Or maybe it’s just me. The Alpha group lot, on the other hand, are great at the second and getting miles better at the first. That’s why they’re on the march and we’re spending all our time filling out grant applications to fix our belfries.

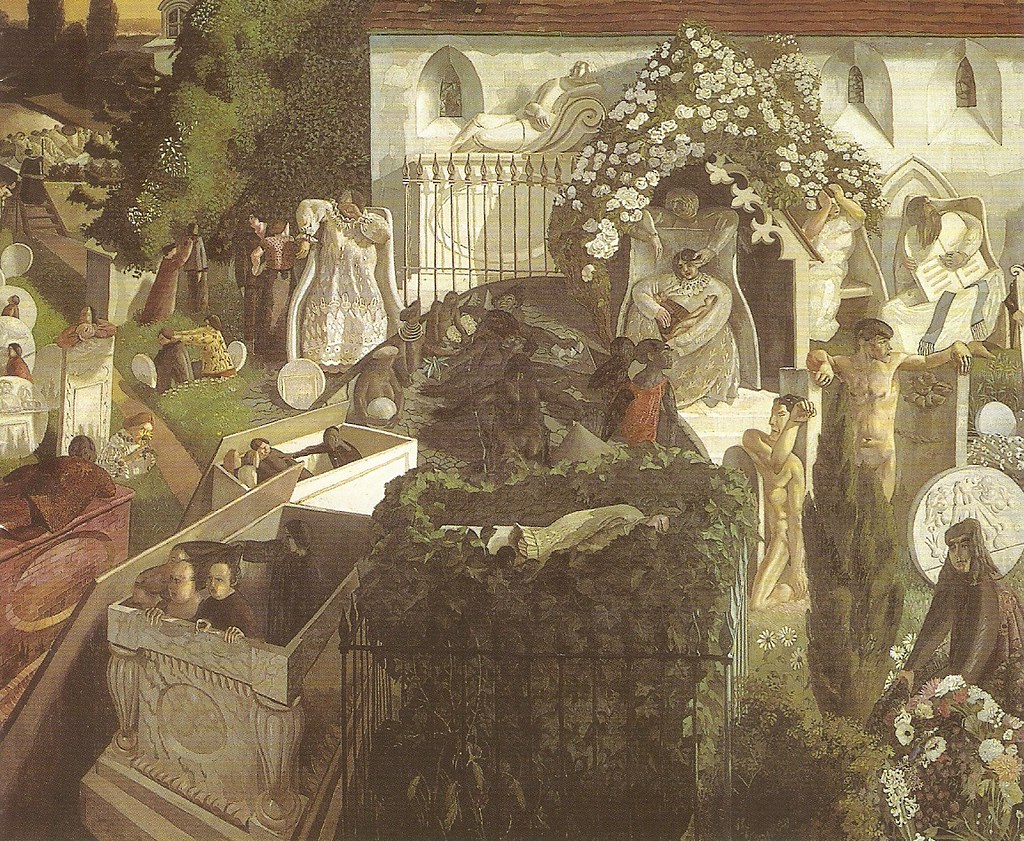

Before closing up shop I read out loud the names of those who have died during the pandemic. It’s a litany of loss. There’s such deep grief and disorientation in our common life as we continue to pass through this valley of the shadow of death.

I start with the names of those who have died but as I kneel there I realise I could go on. I could move onto the falling numbers of baptisms and confirmations, the closure of the church school a few years ago, barely having the numbers any more for the dawn vigil at Easter or midnight mass at Christmas. The fact that my male servers don’t know to take their baseball caps off when they come into church. The loss of the shared assumptions of Christendom.

*

Then a few weeks ago something quite mysterious happened. One Sunday afternoon I let into the church a neighbour who wanted to light a candle for her grandmother, who had died the day before. When she left the church she texted me and I went to lock up, passing though the vestry one way and then the other as I returned to the vicarage. I say this because as I walked back through the vestry after locking up everything was in order.

I spent the next hour or so writing all the names of those who had died in the pandemic into our new Book of Remembrance. These were names that we had collected through our grief circle during the first lockdown as well as the names of those I had been given over the course of the year. As I finished transcribing them I remembered that my neighbour had also put her grandmother’s on the list and I went back into the church to retrieve it.

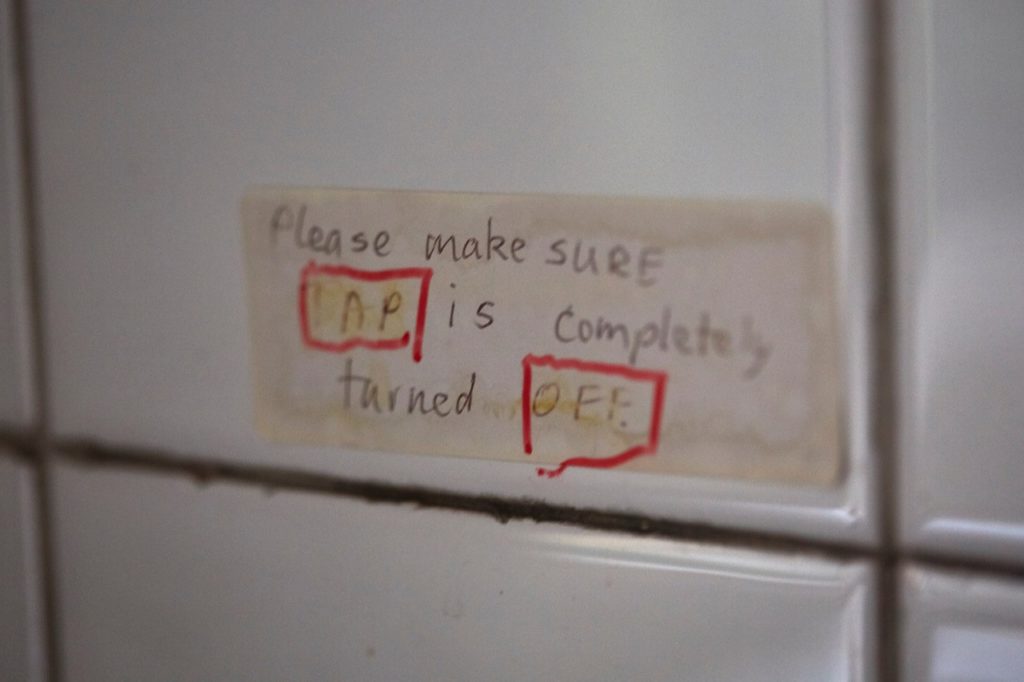

As I opened the vestry door from the vicarage I stopped in my tracks. There was a gushing sound. It was the sound of water. But this time it wasn’t coming from the roof, it was coming from the sink. The tap was on. Someone had turned the tap on. But no one had been in the vestry! Had I turned it on and forgotten to turn it off?

What did this mean? My wife thinks it’s the intervention of St Bridget working through a couple of Irish florists in our church hall. My churchwarden wonders whether we should check the water pressure in the pipes. My daughter worries I’m losing my marbles.

I find it a strangely encouraging sign. I am reminded that we are in touching distance of forces in nature that we are only barely aware of, those energies in the imaginal realm that are waiting to be summoned to our assistance as we come out of the pandemic. There, in our midst, is a bubbling and a fermenting.

It appears that the church may not only be an ark to escape the storm, but also a pumping station, irrigating the parched earth with tears of lament, turning the wilderness into a pool of water and the dry land into fresh springs. Maybe this is what we’re for.

all photos thanks @kristinperers