Ash Wednesday in New Zealand

On Ash Wednesday I was in Wellington, New Zealand. I was visiting my daughter, who was working at the time for a performance arts festival and it was the opening night.

I don’t think I’d ever been to a performance arts festival before. This one took place around a collection of storage containers along the waterfront, a liminal zone if you like, where different artists engaged audience members in a variety of singular provocations.

You could have your chest hair shaved in order to help you think about what it means to be masculine or you could wash your hands with bars of soap etched through with racial slurs to help you reflect on your own unconscious prejudices. Where there was a boundary there was a performance artist to hand to help you cross it.

A little earlier in the evening I had gone to the Ash Wednesday ashing service at the cathedral, itself a kind of performance art piece. You are invited to line up in front of a robed stranger so that they can smudge your forehead with soot and tell you that you are going to die.

The following day, the last of February, I flew back to London. I noticed that flights from China were cancelled into Auckland and there had been a run on antibacterial gel at Dubai Airport.

Coronavirus was nonetheless already making its way across the oceans of the world. The first cases had been reported in the UK at the end of January and we recorded our first virus related death on 5 March. That was just before the second Sunday in Lent.

I wasn’t in church the following Sunday, the third in Lent, because I had a slight fever and a new cough and I went into self-isolation. By the time I came out the other side the country was in lockdown and the archbishops had told us to close up our church buildings for the foreseeable future.

The government started a daily news briefing which opened each time with the latest grim litany of numbers of those who had died.

And then at the beginning of Holy Week the Prime Minister himself was taken into intensive care. We all felt the shock of it. Was this it or would he pull through?

On Easter Sunday he emerged from the wards to thank the NHS for saving his life and to tell us that it could have gone for him either way.

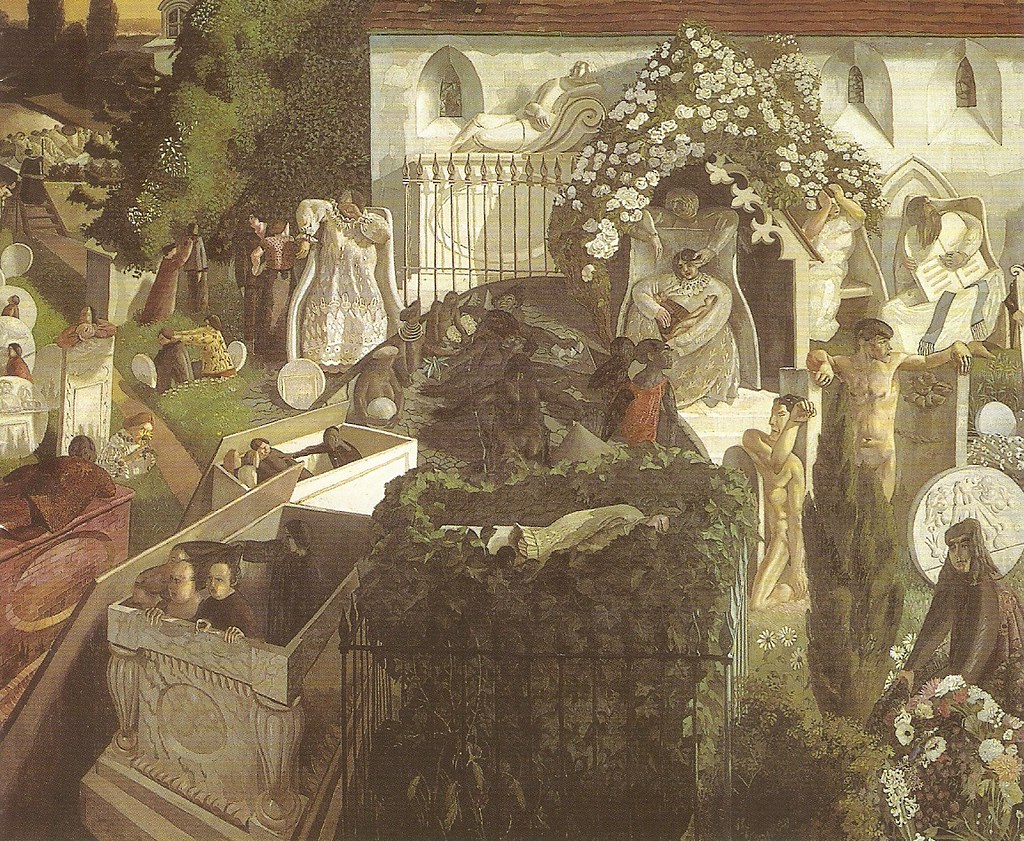

Of course, in the end, there’s only one way it’s going to go for each of us, but we carry on as as though this is a unwelcome provocation. Death is still that boundary we all need to cross.

If Lent provided us with an opportunity to inhabit this liminal space then now that we’re in the season of Easter we can see that it’s not performance art after all. It’s life itself and it’s a beautiful and painful thing.

in memory of Rabbi Avrohom Pinter 21 January 1949 – 13 April 2020.